Darllenwch y dudalen hon yn Cymraeg

In this blog I wanted to talk a little about hospital statistics, which have been so crucial for the understanding of this pandemic.

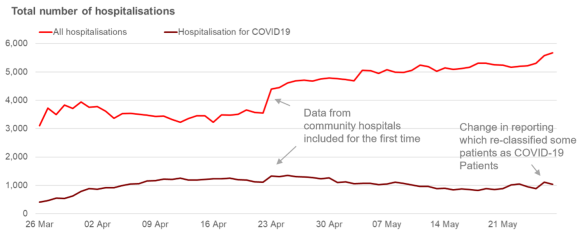

A wide range of metrics have become common currency in public debate over the past few weeks: the number of deaths, the number of positive COVID-19 cases, the number of tests being undertaken. Another important metric which you will have seen being used in Welsh Government press conferences, and in the slides presented every day by the UK Government, is the number of people in hospital with COVID-19. This is an important figure in telling us how many people are in hospital, and therefore the pressure on the NHS and the potential impact on our critical care capacity if the health of those patients deteriorate. The number of people in hospital is also one of the measures that can be used to understand and model whether the measures that are in place are slowing down the transmission of the virus.

Changes to the hospitalisation measures

We’ve recently changed how we’re capturing data on the number of people in hospital, and this has had an impact on the time series you will have seen published for Wales. When a patient is admitted to hospital, their symptoms will be identified by clinicians who will consider if the patient is showing symptoms of COVID-19. When the data are reported nationally to us on a daily basis, we ask health boards to categorise whether patients are a confirmed COVID-19 case (i.e that they have been tested positive for COVID-19) or suspected to have COVID-19. The number of people in hospital has been reported as the combination of these patients.

Since last Monday (25 May) we have asked health boards to change their daily reporting to us. We have now asked them to separate out patients who are recovering (and are rehabilitating). This has been done because recovering patients in rehabilitation, may be nursed in different ways, in different locations and it is important to understand this.

Furthermore, some organisations were already moving recovering patients from their data on COVID beds to non-COVID beds in their reporting. This gave us a misleading understanding of both the trends in COVID patients, and in terms of the demands on the NHS from non-COVID patients. By making the changes to reporting we will achieve a clear and consistent picture across Wales of the impact of COVID on capacity.

In the short-term it has meant some discontinuities in the time series most notably on May 22 and May 26 as health boards moved patients back from “non-COVID” pathways to a COVID pathway. This can be seen in two clear spikes in the series. In future we will be drawing out the different categories clearly in our figures.

Getting our language right

Over the past few weeks much has been spoken of critical care capacity and usage. It’s important to understand what this means. Pre-COVID our NHS capacity would have been at around 150 critical care beds. Since preparations were made for the NHS to be ready for significant pressure on critical care capacity as a result of the pandemic, health boards identified “surge capacity” which has resulted, at times in around 400 beds being available for critical care use. This included general and acute beds that had some intensive care provision, such as mechanical ventilators, attached. This surge capacity is crucial for providing the breathing support that patients would need under significant COVID-19 complexities, but those beds are not in critical care units. Therefore to ensure we are presenting the data as accurately as possible we have started using terminology around “Invasive ventilated beds” instead of “Critical care beds” in reporting.

Some thoughts on data quality and transparency

We are in remarkable times and this has led to unprecedented demand for information, in real-time, about the impact the pandemic is having. As a result statisticians, and the people who provide us with data, are having to produce data at a rate which would have been unimaginable just 3 months ago. This was brilliantly described by the Director-General for statistics regulation, Ed Humpherson, in his recent blog. We are seeing data collected from schools daily and published within hours of receipt. We are seeing the NHS provide daily reports that contribute within hours to publications and press conferences. These are data being gathered, at pace, through administrative systems by critical workers whose primary objective has to be to deliver safe care and interventions to the public.

We know from long experience that administrative data needs to be handled with care, validated and challenged, to ensure what is being counted is what we thought was being counted. That is why there is often a lag between the period to which data relate and official statistics publications that follow.

However at this time, we don’t have the luxury of weeks (or even hours) for validation, and as a result I think it is only fair to those people providing these data that I should be clear – we cannot expect these data to be perfect all the time. We should expect there will be some revisions to data as guidance is continuously being clarified and the resulting statistics are scrutinised. Nevertheless the benefits of transparency and openness at this time is paramount and the public have a right to expect to understand what is happening in their NHS. Therefore we and other government departments are publishing a range of “management information” albeit with appropriate health warnings. Our job as government statisticians is to do as much as we can to explain clearly and openly the limitations of those data, and to be transparent to users when we identify issues, as I have sought to do above.

Glyn Jones

Chief Statistician

Email: stats.info.desk@gov.wales